Day Nine

Tuesday, 09-07-04

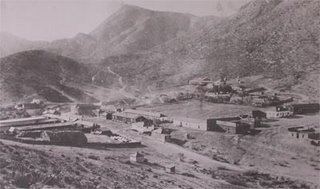

We were up early and excited to begin the day that would see us at our appointed goal; Apache Station at Fort Bowie. Once again we elected to bypass Stien’s Pass Station in favor of focusing on getting some road behind us before it got too hot. The roads were easy to locate and since Paul had already been here before, we made good time in finding the gravel road that led back to Fort Bowie. Below is a good view of the approach to Apache Pass and the surrounding landscape.

It is difficult to appreciate from this picture the total lack of water. The temperature was rising rapidly and even as I stood there still cold from the morning ride, it was clear that the day was going to be hot.

A few miles further and we were on the dirt road headed up through a vaguely defined pass. In a most unlikely place Paul pulled over into a small parking area with a sheltered sign.

The sign gave directions into the park. This 1000 acre park has only foot access for the visitor. Somehow, this seemed fitting to our quest. After over 1800 miles of back road riding it allowed us to savor the final couple of miles in a way that the act of simply driving up and parking at the Fort could have never accomplished.

As we wound our way down the path and into the high desert terrain Paul reminded me that on his last visit there had been prominent signs posted warning of the dangers of mountain lions seen recently on the trail. We hadn’t noticed any warnings this time but it brought a sense of immediacy to our surroundings and since it was still quite early in the day there were no signs of other humans either. The walk was guided by informational markers and we stopped occasionally to enjoy the identification of some of the rich diversity of plant life.

the dangers of mountain lions seen recently on the trail. We hadn’t noticed any warnings this time but it brought a sense of immediacy to our surroundings and since it was still quite early in the day there were no signs of other humans either. The walk was guided by informational markers and we stopped occasionally to enjoy the identification of some of the rich diversity of plant life.

At some point we entered a draw and worked our way through the willow and mesquite. Climbing up onto a gently sloping hillside we could see the old road exiting the chaparral and tracing a path towards a gentle pass in the distance.

Almost without knowing it, we found ourselves walking along a well preserved remnant of the original Butterfield road as it entered a small valley. Where the foot trail crossed the road was a marker and nearby the remains of a stone and adobe foundation and fireplace. The marker read, “Apache Pass- Butterfield Station”

Just beyond the road was a well tended graveyard with a picket fence. It was an ideal location for our last station. So isolated and completely without elaboration. No people, no buildings. Just the wind sighing through a large oak nearby and rustling of desert scrub which led the eye into the rising red rocks beyond.

Just beyond the road was a well tended graveyard with a picket fence. It was an ideal location for our last station. So isolated and completely without elaboration. No people, no buildings. Just the wind sighing through a large oak nearby and rustling of desert scrub which led the eye into the rising red rocks beyond.

For most of its short history the Butterfield Mail run operated under aegis of the numerous Indian chiefs that allowed its passage un-accosted. Preferring to extract some benefit from the station operators, they most often developed a cooperative arrangement. As was mentioned, in Oklahoma, a toll was exacted on the passage of every vehicle or animal on numerous crossings or stops.

In the Arizona territories, this benevolence was extended under the piercing gaze of the famous Chiricahua Apache Chief, Cochise. He had allowed the Butterfield company to build their station in Apache Pass, as long as they agreed to site it some distance away from an important water source nearby. He was cautious to insure that access to the spring was maintained.

In the Arizona territories, this benevolence was extended under the piercing gaze of the famous Chiricahua Apache Chief, Cochise. He had allowed the Butterfield company to build their station in Apache Pass, as long as they agreed to site it some distance away from an important water source nearby. He was cautious to insure that access to the spring was maintained.

Cochise kept peace with the Anglo-Americans even providing firewood and other services, until 1861, when he became their implacable foe because of the blunder of a young U.S. Army officer, Lt. George Bascom.

In that year, Cochise and several of his relatives had gone to an encampment of soldiers in order to deny the accusation that they had abducted a child from a ranch. The boy was later proved to have been kidnapped by another band of Apaches. During the parley, Cochise and his followers were ordered held as hostages by Bascom, but Cochise managed to escape almost immediately by cutting a hole in a tent. Bascom later ordered the other Apache hostages hanged, and the embittered Cochise joined forces with Mangas Coloradas, his father-in-law, in a guerrilla struggle against the American army and settlers.

It was during this time that the only documented Indian attack on a Butterfield Stagecoach ever happened. To be sure other stage lines were attacked and riding through Indian Territory by any conveyance was considered hazardous. It is interesting to note however, that much of our perception about stagecoaches under siege, bullets flying the feathered shafts of arrows pin-cushioning the hapless coach and driver are mere movie myths conjured for the their obvious matinee effect.

As we stood at the ruins it was all too easy to feel how surrounded the hapless Lt. Bascum must have felt as he retreated to the meager protection of the adobe walls of the station. After Bascum had killed Cochise’s brother and two nephews. Cochise retaliated by capturing and later killing Butterfield driver James Wallace as well as four other hostages that Cochise unsuccessfully offered as a trade for his family.

James Wallace is probably buried in the nearby cemetery. It was the post cemetery and when Fort Bowie was abandoned many of the soldiers buried there were disinterred and removed to the National Cemetery in Washington. Some graves remain including one marked Little Robe, Geronimo’s two year old son. There was also this one of a boy from St.Joseph, Missouri, our home town. Born on my birthday. Killed by Indians.

There was also this one of a boy from St.Joseph, Missouri, our home town. Born on my birthday. Killed by Indians.

Fort Bowie, whose initial construction began in 1862, played an integral roll in the shaping of events and as the headquarters of the Anglo’s effort to capture Cochise. Though the National Monument is dedicated to this fight the heart of site itself is its association with Apache Springs.

It is difficult to over state the importance of this fresh water spring.

This rare and dependable water source was key for the Apache people (and pre-Apache civilization) in the region. Its constant supply of fresh water, and location near a common travel route - used by both the native peoples traveling in the area, as well as white settlers journeying west - made it a much used and fought over site. Apache Spring has been partially diverted to provide water to a neighboring cattle ranch. The remaining flow trickles through the riparian area along the bottom of Siphon Canyon, and disappears into the sandy substrate. No photographs are known to exist that would show us what the spring area looked like in a more natural state, but diversion, water development and cattle grazing have had an obvious impact on the spring. Nonetheless, the sound of trickling water still resonates along the footpath adjacent to the Spring. Paul and I approached the quiet cool ravine where it’s music has played to every grateful traveler for time out of reckoning. Many more famous or infamous folks than these two brothers on bikes but none more satisfied by the experience. I filled a small plastic bottle with the water from this sacred and ancient place and we traveled on towards the Fort.

The Fort Bowie of today is a soft shadow of the noisy military stockade it was in the Cochise era. The adobe walls though stabilized seem to be slowly melting into the open space of the parade ground. We were disappointed to find the Ranger Station and Museum were locked and devoid of humans. But then, we just settled onto the porch and realized how lucky we were to be there  alone and had a wonderful moment of complete and uninterrupted silence. It was a rich.

alone and had a wonderful moment of complete and uninterrupted silence. It was a rich.

Paul had brought a postcard with him from Springfield on the very first day. So as to have carried some mail to deliver the whole way. He was hoping to mail it from Fort Bowie back to himself. With the Museum closed we thought we would miss that step but it wasn’t long before some park employees showed up and let us in. The exhibits at the Ranger Station were very interesting and I bought a copy of Ormsby to replace the copy I had pretty much dog-eared that belonged to Paul. We took our time and talked with the Ranger who seemed to have a very good knowledge of the Butterfield Stations in New Mexico and Arizona. He pulled out some maps and we had a great time just looking at his topos of the route. He also told us about a Swedish man who spends a part of every year walking the Butterfield Trail. He encouraged us to find one more station at Dragoon Springs. We thanked him and walked out of the park via a slightly different route.

As we came down the path we had this wonderful view of the old station, the cemetery and the Butterfield winding up towards Apache Pass.

Back at the bikes we made the decision to call this a hiatus in our search for Butterfield Stations, for now. We opted for a slow turn north towards Sedona and Taos and eventually managed to end up spending one night camping down in the Grand Canyon. It was the only time we used our camping gear but the set and setting made it worth carrying it over 4,000 miles. It was also the only time we got rained on. But even that can have its advantage. What a sight!